What I like about Hinduism

What sets Hinduism apart is its all-encompassing nature: there is every kind of name for God and verily every kind of form of God. Everything is God.

Hindus don’t joke when they say they have something like 33 million Gods. That is like a God for every person in small country of 33 million, like

And our practices are catholic. Catholic here means: broad or wide-ranging in tastes, interests, or the like; having sympathies with all; broad-minded; liberal; universal in extent; involving all; of interest to all; universal; relating to all men; all-inclusive.

And because of this, Hinduism does have its mystifying habits, practices and forms. This is largely due to the millennia we have spent looking at the idea of God and contended on how we are to work towards understanding our relationship with this entity. This search for the proper approach to God has seen seekers throughout the ages put forward any and every way of realising God.

In allowing millions of seekers to have had their say on God for over 20,000 years does have an effect on our understanding of the nature of God. Apart from the seers, there have been so many realised souls that no-one actually knows how many there have been. Hinduism is virtually sprouting with realisations of God. Some of the realisations are generic and work across the board. Some don’t.

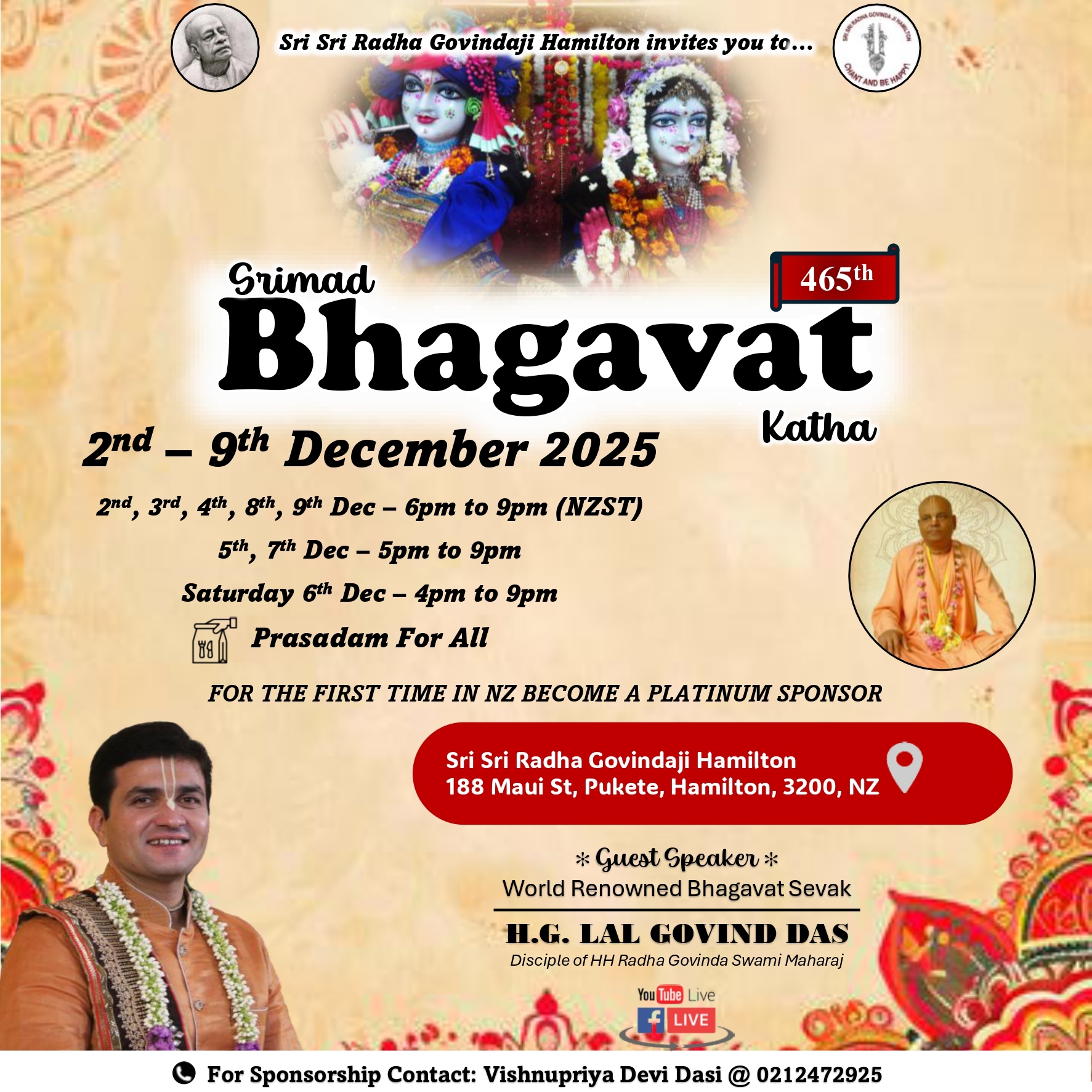

The most common one is the efficacy of the name of God. There is a potency associated with the name of God, a potency verified and accepted by the ranks and file of Hinduism.

For almost all Hindus, the name of God is a mantra in itself. And it can be any one of the millions of name for God. There are also many sayings on this adage: God’s name is more powerful than God himself/herself/itself. The most common of this is “Raam se bada Raam ka naam” (the name of Rama is more potent than Rama himself).

Hindus continually add to their ever-growing pool of names for God. We even have special bhajans (religious songs) called naam sankirtan in which the various names of God are interlaced together to invoke the power of the deity.

The most basic form of worship, in fact, is the chanting of God’s name, not in vain but with a desired purpose behind it. Kids are named after gods, just another way of recalling God when the name is called by anybody. It may seem like a dying trend nowadays but naming children after God is still prevalent in

The name of God is sacred, yes, but also ubiquitous. It infiltrates every aspect of a Hindu’s life, or should. Hindus find, or nowadays try to find, every opportunity to take God’s name. This includes the basic greetings like Ram Ram, Sita Ram, Hari Om,

Then there is praying. We pray in temples, out of temples, in shrines, on the roadside, on the road itself, anywhere and everywhere. It does not matter where one prays, God is everywhere, we say. We see God in rocks, in trees, in the waterways, in the very wind itself.

And prayers can be in any format, including not having a format. You can have formalised prayer session through an intermediary (namely a priest or a sadhu), a congregational prayer session with peers, an individual session or a cry from the heart. In most cases we just get down to it and pray, and hope it is heard.

We also don’t have any problem (well, some of us don’t) in praying to gods of other religions. You want us to pray to Jesus? – no problem. To Buddha? to Allah? no problem. They are but just names of the One.

We can take any religion in this world and find a complementary and corresponding element in Hinduism. The Buddhist element is very well represented in the monastic (sanyasi) traditions and in the raaj yoga traditions.

The love for Jesus/God that Christians have is shown in our bhakti movements. The formless Allah equates to the formless Brahman of the Vedantic tradition. For Hindus, at least. Others may have a different and maybe even a violent reaction to such assumptions.

Even the atheist can feel at home in Hinduism. Generally, atheism is valid in Hinduism, but the path of the atheist is viewed as very difficult to follow in matters of spirituality (Wikipedia).

The Indian Nobel Prize-winner Amartya Sen in an interview with Pranab Bardhan for the California Magazine published in the July-August 2006 edition by the

In some ways people had got used to the idea that

That gave a leg up to the religious interpretation of

Madhava Acharya, the remarkable 14th century philosopher, wrote this rather great book called Sarvadarshansamgraha, which discussed all the religious schools of thought within the Hindu structure. The first chapter is "Atheism" - a very strong presentation of the argument in favour of atheism and materialism. (Wikipedia).

The word Sarvadharshansamgraha means the compendium of every type of path towards God, and every path is considered valid. A path is made valid not only by its practitioner but is made valid through acceptance by practitioners of other paths, who must (and the emphasis is on must) respect the path of every other practitioner.

This, in effect, makes Hinduism a religion that is very much misunderstood and, sometimes, much maligned. This is largely due to the fact that Hinduism has it all: the sublime, the ridiculous and the profane and they can be found together and mostly in harmony with each other in almost all levels of any belief system. All of these levels, by the way, are to be considered valid.

Sublime aspects of Hinduism: the highest philosophies of science, arts and cosmology is available to us. Hinduism guides us to the highest levels of logic, reasoning and intellectual powers by its processes.

Only by using the thinking process can one actually think beyond the process. This is a task of such magnitude that few indeed have accomplished it. Hinduism does this daringly by asking one to remove oneself from the equation when considering the equation.

Ridiculous aspects of Hinduism: some of practices and philosophies are ‘easily disproved’, some even considered childish, especially by outsiders. These are the perplexing stories of the Gods; their families; their apparently ‘human’ weaknesses; the forms of some God (the most lovable being Ganesha, the most respected probably Hanuman); the materialistic elements (offerings and worship for a better job, children, money, etc); the superstitions and the downright contrary (some Tantrik paths which have anti-conventional practices). But all are valid at some level of development, however foolish they may appear to outsiders.

Profane aspects of Hinduism: Hinduism also has its ‘left hand’ path, also considered valid. Aghora elements of incorporating sex, meat-eating, intoxication and other ‘undesirable’ elements are recognised as valid, even if they are looked down upon by the majority. These practices are generally judged for what they deliver to their practitioners and not how they fit in our understanding of what is the right way to worship God.

Most Hindus cannot fault the reasoning behind Aghora practices though they may not agree with the actual practice itself: If everything is created by God, then everything that exists must be perfect, and to deny the perfection of anything would be to deny the sacredness of all life in its full manifestation, as well as deny God/Goddess and the demiGods' perfection. (Wikipedia)

Why is this all possible in Hinduism?

It is simply because the endgame in Hinduism is this: You are God. You may not know it, or know of it, or are unwilling to accept it but you are God.

It is very hard to bring to mind any religion that makes such bold statements with such force. The mahavakayas are given below:

|

Sanskrit: |

English: |

|

Brahman is real; the world is unreal (though mithya is more a mixture of real and unreal rather than just unreal) |

|

|

4. Tat Tvam Asi |

That is what you are, That thou Art (also interpreted sometimes as you are the base (tat)) |

|

I am Brahman (the Absolute) |

|

These are statements of power, to be assimilated and then owned by those using it as mantras. Here you are urged to believe that you are God, and by believing, to become God.

For many this will border on blasphemy, yet for the Hindu it is a fact. Hinduism posits a heaven but only as an interim measure where your good deeds pay some dividends for some time.

Its hell is purgatory – a time of removing the dross of materialism and wickedness from you, and not an eternal pit of fire. You have to come back to mrityu loka (Earth known by its name ‘the world of the dead’) again from heaven or hell to continue on your bid to understand and accept that you are God.

Hindus call this yoga (yoking) with God moksha (liberation), and it equates to Nirvana. It is this yoga with God that we strive for through our numerous lives in all our incarnations. Some are closer to it, others bringing up the rear.

It is also known as Samadhi (equanimity, or equal mindedness).At the first level Samadhi makes you like God (Savikalpa Samadhi) and at a the highest level you become God (Nirvikalpa Samadhi).

This moksha or Samadhi is a realisation of the self's identity with the Absolute or Brahman. It is not becoming God as depicted in the cultural art of

The journey begins with the realisation of the duality of life, that every element of life is made of a thing and its opposite. Day must have night, good must have bad, up must have down for one or the other to operate.

Then it is a matter of making this duality disappear into the awareness of the One. It becomes a matter of realising that everything is but sat chit ananda: being (reality), awareness (consciousness ) and bliss (pure joy).

It is a journey few choose to take. For it also means death: the death of the ego, the little self, the duality of existence. Your existence is wiped out in the yoga with God. The individual personality is dissolved, made redundant, dies because the little self cannot endure the power and the force of the big Self (Atman).

As stated above, to realise the duality of the universe, one has to divorce oneself from that pervasive duality to understand it properly. This is called taking yourself out of the equation to understand the equation.

And on top of it all, the whole caboodle above puts the Hindu in a unique self-effacing position (he has to work towards becoming God but without treading on anyone else’s toes for they are also God).

He has to accept that every other path to God is valid, that any other name or form of God is as valid as his own. What he does with his name and form of God is his business. What others do with their names and forms of God is their business.

Being a Hindu is a solo act, then. An act of personal effort through a self-defined path to a personal goal. For all alone a Hindu has to forge out a form of God, and name it. He then makes a lonely and personal effort to accept it by worshipping it. Finally, he makes the final leap, all alone, in becoming it. All else is of little matter.

Notes

Please note that He/he is generically used here because of convenience. In no way it is insinuated that only men can tread the path to God. Women, it is said, are better equipped to tread the spiritual path because of their innate nature comprising of stoic forbearance, compassion and maternal instincts.

In ancient

Hinduism is replete with great names of women like Gargi, Maitreyi, Aditi, Indrani, Savitri, Andal and Meera and the recently by women of such status as Shantala Devi, the beautiful queen of Vishnuvardhana, Ahalyabai Holkar, the Rani of Indore, [1735-1795], Ananda MoyiMa [1896-1982], and the Holy Mother, Sarada Devi.

- Nalinesh Arun is a former Fiji journalist who lived in India for many years. He is now based in Christchurch

What sets Hinduism apart is its all-encompassing nature: there is every kind of name for God and verily every kind of form of God. Everything is God.

Hindus don’t joke when they say they have something like 33 million Gods. That is like a God for every person in small country of 33 million,...

What sets Hinduism apart is its all-encompassing nature: there is every kind of name for God and verily every kind of form of God. Everything is God.

Hindus don’t joke when they say they have something like 33 million Gods. That is like a God for every person in small country of 33 million, like

And our practices are catholic. Catholic here means: broad or wide-ranging in tastes, interests, or the like; having sympathies with all; broad-minded; liberal; universal in extent; involving all; of interest to all; universal; relating to all men; all-inclusive.

And because of this, Hinduism does have its mystifying habits, practices and forms. This is largely due to the millennia we have spent looking at the idea of God and contended on how we are to work towards understanding our relationship with this entity. This search for the proper approach to God has seen seekers throughout the ages put forward any and every way of realising God.

In allowing millions of seekers to have had their say on God for over 20,000 years does have an effect on our understanding of the nature of God. Apart from the seers, there have been so many realised souls that no-one actually knows how many there have been. Hinduism is virtually sprouting with realisations of God. Some of the realisations are generic and work across the board. Some don’t.

The most common one is the efficacy of the name of God. There is a potency associated with the name of God, a potency verified and accepted by the ranks and file of Hinduism.

For almost all Hindus, the name of God is a mantra in itself. And it can be any one of the millions of name for God. There are also many sayings on this adage: God’s name is more powerful than God himself/herself/itself. The most common of this is “Raam se bada Raam ka naam” (the name of Rama is more potent than Rama himself).

Hindus continually add to their ever-growing pool of names for God. We even have special bhajans (religious songs) called naam sankirtan in which the various names of God are interlaced together to invoke the power of the deity.

The most basic form of worship, in fact, is the chanting of God’s name, not in vain but with a desired purpose behind it. Kids are named after gods, just another way of recalling God when the name is called by anybody. It may seem like a dying trend nowadays but naming children after God is still prevalent in

The name of God is sacred, yes, but also ubiquitous. It infiltrates every aspect of a Hindu’s life, or should. Hindus find, or nowadays try to find, every opportunity to take God’s name. This includes the basic greetings like Ram Ram, Sita Ram, Hari Om,

Then there is praying. We pray in temples, out of temples, in shrines, on the roadside, on the road itself, anywhere and everywhere. It does not matter where one prays, God is everywhere, we say. We see God in rocks, in trees, in the waterways, in the very wind itself.

And prayers can be in any format, including not having a format. You can have formalised prayer session through an intermediary (namely a priest or a sadhu), a congregational prayer session with peers, an individual session or a cry from the heart. In most cases we just get down to it and pray, and hope it is heard.

We also don’t have any problem (well, some of us don’t) in praying to gods of other religions. You want us to pray to Jesus? – no problem. To Buddha? to Allah? no problem. They are but just names of the One.

We can take any religion in this world and find a complementary and corresponding element in Hinduism. The Buddhist element is very well represented in the monastic (sanyasi) traditions and in the raaj yoga traditions.

The love for Jesus/God that Christians have is shown in our bhakti movements. The formless Allah equates to the formless Brahman of the Vedantic tradition. For Hindus, at least. Others may have a different and maybe even a violent reaction to such assumptions.

Even the atheist can feel at home in Hinduism. Generally, atheism is valid in Hinduism, but the path of the atheist is viewed as very difficult to follow in matters of spirituality (Wikipedia).

The Indian Nobel Prize-winner Amartya Sen in an interview with Pranab Bardhan for the California Magazine published in the July-August 2006 edition by the

In some ways people had got used to the idea that

That gave a leg up to the religious interpretation of

Madhava Acharya, the remarkable 14th century philosopher, wrote this rather great book called Sarvadarshansamgraha, which discussed all the religious schools of thought within the Hindu structure. The first chapter is "Atheism" - a very strong presentation of the argument in favour of atheism and materialism. (Wikipedia).

The word Sarvadharshansamgraha means the compendium of every type of path towards God, and every path is considered valid. A path is made valid not only by its practitioner but is made valid through acceptance by practitioners of other paths, who must (and the emphasis is on must) respect the path of every other practitioner.

This, in effect, makes Hinduism a religion that is very much misunderstood and, sometimes, much maligned. This is largely due to the fact that Hinduism has it all: the sublime, the ridiculous and the profane and they can be found together and mostly in harmony with each other in almost all levels of any belief system. All of these levels, by the way, are to be considered valid.

Sublime aspects of Hinduism: the highest philosophies of science, arts and cosmology is available to us. Hinduism guides us to the highest levels of logic, reasoning and intellectual powers by its processes.

Only by using the thinking process can one actually think beyond the process. This is a task of such magnitude that few indeed have accomplished it. Hinduism does this daringly by asking one to remove oneself from the equation when considering the equation.

Ridiculous aspects of Hinduism: some of practices and philosophies are ‘easily disproved’, some even considered childish, especially by outsiders. These are the perplexing stories of the Gods; their families; their apparently ‘human’ weaknesses; the forms of some God (the most lovable being Ganesha, the most respected probably Hanuman); the materialistic elements (offerings and worship for a better job, children, money, etc); the superstitions and the downright contrary (some Tantrik paths which have anti-conventional practices). But all are valid at some level of development, however foolish they may appear to outsiders.

Profane aspects of Hinduism: Hinduism also has its ‘left hand’ path, also considered valid. Aghora elements of incorporating sex, meat-eating, intoxication and other ‘undesirable’ elements are recognised as valid, even if they are looked down upon by the majority. These practices are generally judged for what they deliver to their practitioners and not how they fit in our understanding of what is the right way to worship God.

Most Hindus cannot fault the reasoning behind Aghora practices though they may not agree with the actual practice itself: If everything is created by God, then everything that exists must be perfect, and to deny the perfection of anything would be to deny the sacredness of all life in its full manifestation, as well as deny God/Goddess and the demiGods' perfection. (Wikipedia)

Why is this all possible in Hinduism?

It is simply because the endgame in Hinduism is this: You are God. You may not know it, or know of it, or are unwilling to accept it but you are God.

It is very hard to bring to mind any religion that makes such bold statements with such force. The mahavakayas are given below:

|

Sanskrit: |

English: |

|

Brahman is real; the world is unreal (though mithya is more a mixture of real and unreal rather than just unreal) |

|

|

4. Tat Tvam Asi |

That is what you are, That thou Art (also interpreted sometimes as you are the base (tat)) |

|

I am Brahman (the Absolute) |

|

These are statements of power, to be assimilated and then owned by those using it as mantras. Here you are urged to believe that you are God, and by believing, to become God.

For many this will border on blasphemy, yet for the Hindu it is a fact. Hinduism posits a heaven but only as an interim measure where your good deeds pay some dividends for some time.

Its hell is purgatory – a time of removing the dross of materialism and wickedness from you, and not an eternal pit of fire. You have to come back to mrityu loka (Earth known by its name ‘the world of the dead’) again from heaven or hell to continue on your bid to understand and accept that you are God.

Hindus call this yoga (yoking) with God moksha (liberation), and it equates to Nirvana. It is this yoga with God that we strive for through our numerous lives in all our incarnations. Some are closer to it, others bringing up the rear.

It is also known as Samadhi (equanimity, or equal mindedness).At the first level Samadhi makes you like God (Savikalpa Samadhi) and at a the highest level you become God (Nirvikalpa Samadhi).

This moksha or Samadhi is a realisation of the self's identity with the Absolute or Brahman. It is not becoming God as depicted in the cultural art of

The journey begins with the realisation of the duality of life, that every element of life is made of a thing and its opposite. Day must have night, good must have bad, up must have down for one or the other to operate.

Then it is a matter of making this duality disappear into the awareness of the One. It becomes a matter of realising that everything is but sat chit ananda: being (reality), awareness (consciousness ) and bliss (pure joy).

It is a journey few choose to take. For it also means death: the death of the ego, the little self, the duality of existence. Your existence is wiped out in the yoga with God. The individual personality is dissolved, made redundant, dies because the little self cannot endure the power and the force of the big Self (Atman).

As stated above, to realise the duality of the universe, one has to divorce oneself from that pervasive duality to understand it properly. This is called taking yourself out of the equation to understand the equation.

And on top of it all, the whole caboodle above puts the Hindu in a unique self-effacing position (he has to work towards becoming God but without treading on anyone else’s toes for they are also God).

He has to accept that every other path to God is valid, that any other name or form of God is as valid as his own. What he does with his name and form of God is his business. What others do with their names and forms of God is their business.

Being a Hindu is a solo act, then. An act of personal effort through a self-defined path to a personal goal. For all alone a Hindu has to forge out a form of God, and name it. He then makes a lonely and personal effort to accept it by worshipping it. Finally, he makes the final leap, all alone, in becoming it. All else is of little matter.

Notes

Please note that He/he is generically used here because of convenience. In no way it is insinuated that only men can tread the path to God. Women, it is said, are better equipped to tread the spiritual path because of their innate nature comprising of stoic forbearance, compassion and maternal instincts.

In ancient

Hinduism is replete with great names of women like Gargi, Maitreyi, Aditi, Indrani, Savitri, Andal and Meera and the recently by women of such status as Shantala Devi, the beautiful queen of Vishnuvardhana, Ahalyabai Holkar, the Rani of Indore, [1735-1795], Ananda MoyiMa [1896-1982], and the Holy Mother, Sarada Devi.

- Nalinesh Arun is a former Fiji journalist who lived in India for many years. He is now based in Christchurch

Leave a Comment