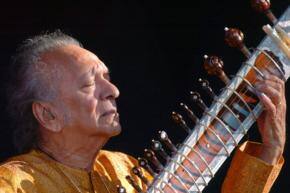

Ravi Shankar: Giant of 20th Century

Ravi Shankar, who has died aged 92, was one of the giants of twentieth century music. As a performer, composer and teacher, he was an Indian classical artist of the highest rank, and he spearheaded the worldwide spread of Indian music and culture.

He achieved his greatest fame in the 1960s when he was embraced by the Western counterculture. Through his influence on his great friend George Harrison, and appearances at the Monterey and Woodstock festivals and the Concert for Bangladesh, he became a household name in the West, the first Indian musician to do so. To a movement challenging accepted values, he symbolised the genius of an ancient, wiser culture.

Yet the Sixties were but one chapter in an unparalleled career of record-breaking longevity. He had first entered the public eye as a ten-year-old dancer and musician performing on the world’s stages, and he was still packing out concert halls this year. Indeed, when he first met Harrison, he was already 46 and widely acclaimed as India’s greatest classical musician.

A Bengali Brahmin, he was born Robindra Shankar in 1920 in India’s holiest city, Varanasi, the youngest of four brothers who survived to adulthood, and spent his first ten years in relative poverty, brought up by his mother. He was almost eight before he met his absent father, a globe-trotting lawyer, philosopher, writer and former minister to the Maharajah of Jhalawar.

In 1930 his eldest brother Uday Shankar uprooted the family to Paris, and over the next eight years Ravi enjoyed the limelight in Uday’s troupe, which toured the world introducing Europeans and Americans (and many Indians) to Indian classical and folk dance, in a foreshadowing of Ravi’s own pioneering of Indian music two decades later.

Ravi had only four years of conventional schooling in total, but his cultural education was mindboggling. Pitched into the glamour and tumult of the Paris, New York and Hollywood highlife, he met Gertrude Stein, Cole Porter, Clark Gable and Joan Crawford. He saw Stravinsky, Toscanini, Heifetz and Kreisler, Shalyapin at the Paris Opera, Cab Calloway at the Cotton Club, Duke Ellington, W. C. Fields and more. As a twelve-year-old dancer, he was praised in a New York Times review.

He was even more blessed in India’s arts. He may have barely known his father but he inherited his restlessness, spirituality and love of music. In Uday’s troupe he worked with some first-class musicians, while Uday himself, who was twenty years older, instilled a love of dance and the stage and a reverence for India’s heritage. The latter was strengthened by an inspirational meeting at thirteen with India’s greatest cultural figure of the twentieth century, Rabindranath Tagore.

But the decisive influence on his life was his music guru. Rejecting showbusiness, in 1938 Shankar began seven years of intensive guru-shishya training with Ustad Allauddin Khan, living under the same roof. This was the period when he began to develop into a musician of uncommon powers. In 1941 he married Allauddin Khan’s daughter, the surbahar player Annapurna Devi. (They had one son, Shubho.) Her brother was Ali Akbar Khan, who went on to become the world’s leading sarod player. In the early 1940s a lucky fly on their Maihar wall could have watched the three students learning music together at the feet of Allauddin Khan – the ancient oral tradition at its best.

During the Forties and Fifties Shankar became a star in India as a scintillating performer on sitar and a leading creative force. He developed a characteristic sitar sound, with powerful bass notes and a serene and spiritual touch in the alap movement of a raga. He was responsible for incorporating many aspects of Carnatic (south Indian) music into the north Indian system, especially its mathematical approach to rhythm. He also gave a new prominence to the tabla player in concert.

He was appointed Director of Music at the Indian People’s Theatre Association, and later held the same position at All India Radio (1949–56). He composed his first new raga in 1945 (30 more would follow) and began a prolific recording career. He wrote a new melody for Mohammed Iqbal’s patriotic poem ‘Sare Jahan Se Accha’ – today a ubiquitous Indian national song. He mounted a theatrical production of The Discovery of India, and formed the National Orchestra (Vadya Vrinda) whose ground-breaking explorations of orchestral playing used both Indian and Western instruments. He was soon providing award-winning film scores; Satyajit Ray invited Shankar to compose for four of his movies, including the Apu Trilogy. In the traditional manner, he also took on his own music disciples, teaching them through the oral tradition, and never charging. He continued teaching in this way throughout his life.

Believing in the greatness of Indian classical music and blessed with charisma and intelligence, he pursued a dream of taking the music out to the Western world. Between the early 1950s and the mid-1960s he became the leading international emissary for Indian music, first performing as a solo artist in the USSR in 1954, in Europe and North America in 1956, and Japan in 1958. Yehudi Menuhin, John Coltrane and Philip Glass, among many others, fell under the spell of his music. He built his audience by relentlessly touring small venues and releasing records. Meanwhile his star continued to rise at home, with more Bengali movie soundtracks, two notable Hindi films too (Anuradha and Godaan), his own music school in Bombay, new stage productions Melody and Rhythm, Samanya Kshati, Chandalika and Nava Rasa Ranga, as well as regular concerts and broadcasts.

The connection with George Harrison from 1966 took him temporarily to a level of superstardom. Thereafter he spent increasing amounts of time in the West, but he never lost his roots, and was shocked by how superficially Indian culture was portrayed by some. Happily, after the hysteria died down he retained a long-term international following of serious enthusiasts, which continued to grow. Probably his most long-lasting achievement was to establish this new audience outside India for hundreds of other Indian musicians who followed in his footsteps. This assisted musicians from other countries too; Harrison later called Shankar ‘the Godfather of World Music’.

He remained lifelong friends with Harrison. In the early 1970s they collaborated on two albums and toured the USA together. They also organised the Concert for Bangladesh in 1971, the forerunner of all charity concerts, which highlighted the plight of Shankar’s fellow Bengalis during the liberation war.

Thereafter both were considered heroes by Bangladeshis. They worked together again on later projects, in particular the 1997 album Chants from India, and Harrison co-produced the excellent box set retrospective Ravi Shankar: In Celebration. Shankar’s impact was felt on other musical traditions too. His work with Yehudi Menuhin on West Meets East earned them a Grammy, and he was commissioned by the London Symphony Orchestra to write a concerto for sitar and orchestra. He later wrote a second sitar concerto for the New York Philharmonic under the direction of Zubin Mehta. He composed works for flautist Jean-Pierre Rampal, cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, shakuhachi master Hosan Yamamoto and koto virtuoso Musumi Miyashita. In a 1987 concert held inside the Kremlin, he wrote beautiful music for Russian orchestral, choral and folk singers to perform alongside Indian classical players. His influence on Philip Glass was such that Glass considers Shankar to be one of his two principal teachers. Later they would collaborate on the 1990 album Passages, and on Orion for the Athens 2004 Cultural Olympiad.

A long-term ambition was to establish an ashram-style home and music centre in India where selected students could live and learn. His first effort at this was in Varanasi in the 1970s. Then, after composing the music for the 1982 Asian Games in Delhi, he moved to the capital, eventually building the Ravi Shankar Centre in Delhi in 2001, which today hosts an annual music festival.

His first marriage ended in divorce in 1982, following many years of separation. As he admitted, his private life was complicated then. There were long-term relationships with Kamala Chakravarty and with Sue Jones. Eventually in 1989 he married Sukanya Rajan, who became a source of enormous strength for him. They divided their time between Delhi and San Diego. A tragedy occurred in 1992 when his son Shubho, a sitarist who had performed with his father at times, died unexpectedly at the age of 50. Later Shankar took great pride in seeing his two musician daughters achieve world renown in different fields: the multi-Grammy winning Norah Jones (daughter of Sue Jones) and the Grammy-nominated sitar player Anoushka Shankar (daughter of Sukanya). Anoushka often accompanied him in concert.

He was the author of three books: two in English, 'My Music, My Life' and 'Raga Mala' (the latter an autobiography), and 'Raag Anurag' in Bengali. In latter years he received numerous awards, principal among which were probably the Bharat Ratna, India’s highest civilian award, France’s Commandeur de la Légion d’Honneur, and an honorary knighthood from Britain. His film score for Richard Attenborough’s 'Gandhi' was nominated for an Academy Award. Another kind of nomination came from Rajiv Gandhi, who appointed him as a member of the Rajya Sabha, India’s upper house of parliament, from 1986 to 1992.

If he could walk with these kings and prime ministers, he never lost the common touch. Friends loved his impish sense of fun, which complemented his air of dignity and authority. In the words of the filmmaker Mark Kidel, who produced an award-winning 2002 documentary on Shankar, he had ‘a marvellously light touch and a strong spiritual core’.

He never contemplated retirement, and every year arranged tours. In the tradition of Indian music one never stops learning, and he gave the lie to the notion that age must bring a diminishing of creativity.

In 2009 he said, ‘I feel very strongly that I am now a much better musician than ever before, so much more creative. Maybe I don’t have the same speed or stamina of youth, but believe me, I have trouble sleeping these days because so much music is going through my head.’ Thus his 3rd sitar concerto was premiered by the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra in 2009, and at the age of 90 he composed his first symphony for sitar and orchestra, premiered at the Royal Festival Hall by the London Philharmonic under the baton of David Murphy.

The sitar soloist for both of these performances was Anoushka rather than Ravi, a sign that while the nonagenarian’s creative reserves were overflowing, his energy levels could not always keep up. Nevertheless he repeatedly bounced back from major health troubles to reappear in concert halls. Audiences would watch nervously as a frail old man was helped on stage, only to be amazed by the transformation that music brought upon him. In his last concert, on November 4th in Long Beach, California, he required a wheelchair and an oxygen supply, but once he started playing his vitality and magic returned.

At a time of music industry change, he set up his own label that has issued fascinating archival releases and a live album recorded at home (which has just received a 2013 Grammy nomination). The symphony appeared on CD (The Independent deemed it ‘a resounding triumph’), and there are DVD releases of his feature-length 1968 documentary Raga and a film of his 2011 Escondido concert. The music never stopped and it is hard to believe it will now.

In 2011 the Los Angeles Times ventured that ‘Music may not have, precisely, saints. But no musician alive is a closer fit.’ It’s a verdict that he would have rejected, but the millions whose lives he touched may agree with it.

He is survived by his wife, two daughters, three grandchildren, and four great-grandchildren.

(Oliver Craske is a writer and editor. He was an invaluable resource and provided additional narrative for Ravi Shankar’s autobiography, ‘Raga Mala.’)

The Obituary is courtesy The Ravi Shankar Foundation.