Finding Common Ground With India In Turbulent Times

If you are looking out at the world right now with some trepidation, you’re not alone.

The behaviours we have come to expect from the leaders of major powers and between states have changed markedly in 2025.

And despite appearances, it is not all down to US President Donald Trump, tariffs or what is happening on the Signal messaging app.

For a couple of years now, experts have been analysing the changing dynamics across our region.

This has included a hardening political temperament among formerly liberal countries in the west, a shift away from established multilateral institutions towards bespoke smaller sub-regional groupings, and a swing towards competition and nationalism as the new normal.

China’s rise and the efforts of the United States to retain primacy are the two big drivers of these changes, but they are not the only ones.

Across Asia and the rest of the developing world, there have been murmurings for some time now that the system of relationships, rules and organisations that worked well in the post-1945 era has served its purpose and now needs a revamp.

Rising powers want a greater say and are tired of being judged by what they see to be a narrow – predominantly western-formed – rule book.

The big question in 2025 is the degree to which countries will be prepared to see major changes to the rules and norms governing our region or whether some may choose to dig in to defend their preferred world order.

There is no script for what is happening. It is a live debate, with globalisation, democracy, rights and liberalism mixed with international law, economics, and politics.

Although many countries arguably remain committed to the higher objectives of the post-1945 world order, the extent to which they are prepared to actively defend it against clear challenges to the status quo is yet to be determined.

It is already evident that a number of countries – China, Russia, Israel, the US, and others – are working to secure their own interests, including over the sovereign territory of others that they deem essential for their own security.

High-level visits and military exercises are putting these interests on full display, including – for New Zealand – in the Tasman Sea where China has just conducted a live-firing military exercise right under the main trans-Tasman flightpath.

The natural response of any smaller state is self-protection, and it appears few states are taking their chances.

Many countries, including New Zealand, are examining their military expenditure to ensure they have sufficient capability to defend their territory or at least deter unwanted incursions.

Smaller countries like ours are also rapidly advancing strategic partnerships that shore up important relationships, retain access to important markets and open new ones, and that give us a better understanding of other countries’ priorities and interests so we can better protect our own.

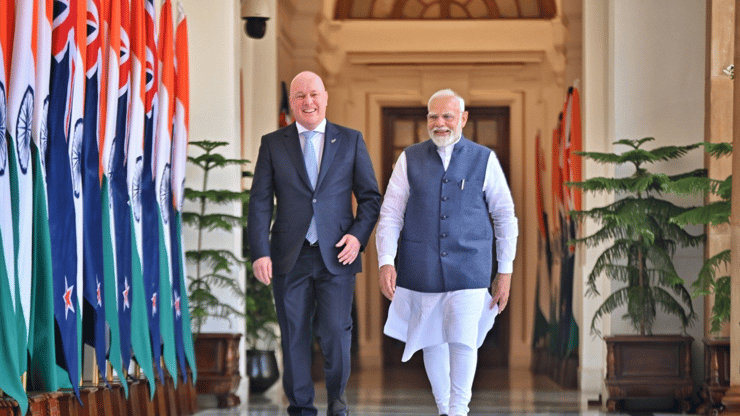

It is in this context that I was particularly interested to join the recent Prime Minister Christopher Luxon-led delegation to India.

There has been plenty of coverage of the visit itself and the many outcomes announced, but it is also interesting to examine the New Zealand-India relationship in the context of our changing region and where India is seeking to position itself in this new world dis-order.

I came away with three main observations.

First is that India sees this moment not as a descent into chaos but an opportunity to ascend as a leader and establish itself as an independent power. It sees itself in a region less centred on the United States and more focused on multiple poles of influence.

While believing in the need for multilateralism, India wants to make its own choices and is open to regional order and rules shifting to better accommodate rising powers.

In short, India is looking at the world today with strategic optimism and as a moment to better define itself as a major power.

The second is that nationalism, heritage and culture are starting to play a bigger role in an order where regional power centres are being tested and rebuilt.

In India’s case, we are seeing a growing number of references to heritage and culture informing India’s foreign policy, and greater outreach to Indians living abroad as an extension of that policy.

Less concerned with establishing norms and initiatives that fit within western paradigms or initiatives, India – just like China – is cultivating its own domestic and regional objectives that are proudly and unashamedly Indian.

The concept of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam – broadly meaning the world is one family – was used as the motto for India’s hosting of the G20 Summit in 2023. The term comes from a Sanskrit text, drawing on the wisdom of Hindu gods.

The third is that despite these two observations, at a bilateral level India is showing greater pragmatism.

Look no further than the Free Trade Agreement negotiations recently announced between India and New Zealand.

For many years India has made it clear that it is not interested in negotiating a trade deal with New Zealand that includes goods access.

Yet today, in a much more volatile regional order and tougher trade environment, India is acknowledging that it too benefits from having a diversity of partners and needs to take a case-by-case approach to building relations.

India is also showing that it has a role to play as a regional leader, providing ways for smaller countries to connect into India’s orbit, and moving much more quickly than it has done previously to come to the aid of others.

Two notable examples include its decision to help underwrite Sri Lanka during its recent debt crisis, and just this week, within hours of the Myanmar earthquake, despatching many tonnes of disaster relief and medical supplies to Yangon.

The India-New Zealand relationship today characterises the rewards of thoughtful strategic diplomacy on both sides.

For New Zealand, our relationship with India not only serves our own strategic interests, as it does India’s as an emerging pole in our region, but also contributes to the larger goal of buttressing regional peace and stability at a time of great upheaval.

(This was first published in Newsroom. Suzannah Jessep is chief executive of the Asia New Zealand Foundation)