Embracing The Diversity Of Language In South Asian Theatre

Members of New Zealand's South Asian communities are preparing to put on theatre performances in their native languages to celebrate a couple of important cultural festivals over the next week.

While Hindi is the most-common language spoken in India, another 21 languages are officially recognised in the constitution, including Bengali, Gujarati and Marathi.

The communities in New Zealand that speak these languages are increasingly performing in their native tongues.

The Auckland Marathi Association is hosting an Ashadhi Ekadashi festival featuring theatre performances in Mangere Bridge on 17 July.

Meanwhile, the Probasee Bengali Association of New Zealand is performing a play titled Awghoton ... Aajo Ghote to mark the 25th anniversary of Natok at Spotlight Theatre in Auckland's Manukau on 20 and 21 July.

"Natok" is a Bengali word used to describe a play or a type of theater in Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal.

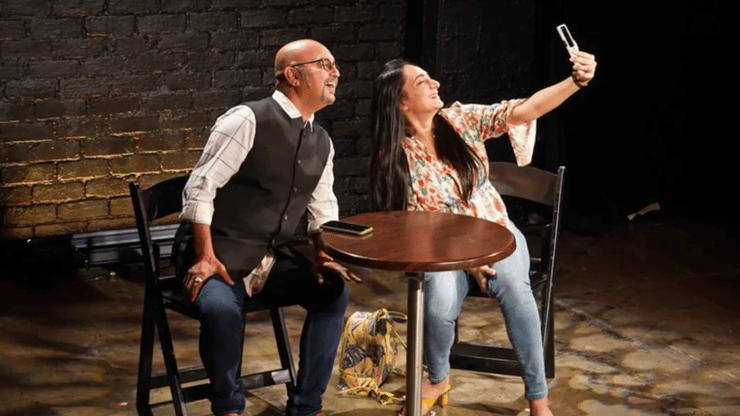

Members of the Probasee Bengali Association of New Zealand take part in a rehearsal for a play titled Awghoton ... Aajo Ghote. Photo: Swayam Sarkar

Amit Ohdedar, founder of the Probasee Bengali Association of New Zealand, has watched the community grow for more than 25 years.

"The very fact that we've been able to sustain doing plays for 25 years definitely shows the demand within the community," Ohdedar says. "That's motivation, that gives you hope."

The association was founded in 1999 after New Zealand saw a surge of Bengali migrants following the Immigration Amendment Act in 1991.

Ohdedar says the silver anniversary reflects a desire to keep the spirit of Bengali theatre alive in Aotearoa.

Performing theatre in Bengali helps preserve the community's lingual culture, he says.

"We are constantly fighting [the dominance of Hindi] to retain our identity, because we are a minority within a minority," Ohdedar says.

Sananda Chatterjee, assistant director of the Natok Anniversary performance and a member of the Probasee Bengalee Association of New Zealand since 2003, agrees on the importance of Indian regional languages.

"Language is very important to any migrant," Chatterjee says. "Languages of a place are so imbued with cultural practices, it's crucial to maintain your heritage."

For the Bengali community living in New Zealand, theatre is more than just a form of entertainment. It's a means of connectivity.

"It's relevant for second- and third-generation kids who have no other way of immersing themselves in their culture," she says.

A scene from a play titled RangGheli at Basement Theatre in April. Photo: Shailesh Prajapati

Chatterjee characterizes Bengali plays as one of the older forms of theatre in India, derived from jatra, a popular folk theatre in the region.

"There used to be travelling groups. It's rooted in socialist theatre, which was performed on the streets," Chatterjee says. "I find it super melodramatic, the overacting works - you almost want to dial it up."

Prashant Belwalkar, former president of the Auckland Marathi Association, says Marathi theatre is an equally powerful medium of communication in the community.

"Most of the communities in Maharashtra, they grow up with a localised theatre, that's the way Marathi theatre connects to the community," Belwalkar says.

The Auckland Marathi Association celebrates its heritage through theatre, especially during significant cultural events such as Ashadhi Ekadashi.

This festival, observed on the 11th lunar day of the bright fortnight of the Hindu month of Ashadha, is an occasion for the Marathi community to come together and honor their traditions through performances that are rich in cultural significance.

Belwalkar has been performing Marathi plays in Aotearoa since migrating in 2001 to keep the theatre environment alive in the community.

"The community members themselves want to take part and have committed time and resources; the dedication has not reduced a bit in the last 20 to 25 years," Belwalkar says.

"The next generation over here in New Zealand would not be exposed to a lot of [Indian regional] theatre as kids as we grew up, our own diaspora will not have that opportunity, meaning that art would be lost to our next generation."

The cast and crew of Chuk Bhuk Dyavi Ghyavi, directed by Gaurav Sawant. Photo: Santosh Suresh Jain

Gaurav Sawant, a Marathi writer and director and former secretary of the Auckland Marathi Association, agrees on the importance of these performances to the community.

"Our stories resonate a lot with our people here in the community, having something from their language, experiences that are particular to them being performed on a stage or to a larger audience," Sawant says. "It gives them a sense of pride."

In addition to performing for the Marathi community, Sawant also highlights the significance of appealing to broader audiences.

"For our stories to be heard, we need to put in an effort," he says. "Not all the events that have happened to us in India, people here [in New Zealand] will understand.

"Groups like Prayas and Indian Ink theatre company have done work to help put us on the map. They give us hope that if we consistently produce high-quality theatre, we will get bigger in New Zealand."

Shailesh Prajapati, former president of Gujarati Sahitya Mandal NZ, collaborated with other directors to produce an anthology of plays titled Our Stories, Our Plays entirely in Gujarati at Basement Theatre in Auckland's CBD in April.

Prajapati says his own language struggles upon arrival in New Zealand have coloured his experience.

"In 2003, I migrated and left everything behind," he recalls. "I struggled with English, as it's my second language. My education had been in my own language."

His first Gujarati play in New Zealand was in 2013, a production he insisted on performing in Gujarati as he was interested in preserving linguistic heritage.

"I always do Gujrati stories in Gujrati language," he says.

"I always try to find different subjects, contemporary theatre as well as selecting plays they haven't seen before, which brings the Gujarati culture."

Prajapati says that the native use of his language engages the Gujarati audience he's performing to.

"[The Gujarati immigrant community] misses their culture, and so once someone brings that to their plate, they are so happy," he says.

"They reconnect with their roots. Instead of watching a Gujrati play translated into English language, they want to see Gujarati speaking, living people."

* Nabeelah Khan is a recipient of the 2024 RNZ Asia scholarship.